David Jones scales the heights

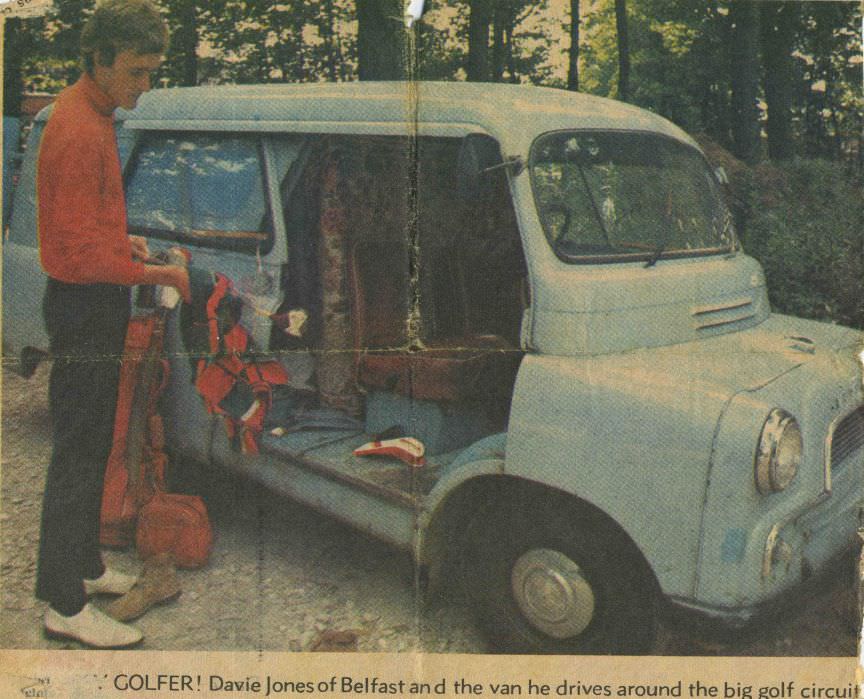

This is what being a touring professional golfer entailed for the young David Jones — a builder's van. a set of clubs and a dream

It really is true that a picture is worth a 1,000 words. Not only does it sum up the young man that was David Jones, but also perfectly tells the story of what was a humble start to a great PGA career.

Aged around 21, the 6ft 5in Bangor native stands beside the vehicle he was to drive around what the newspaper caption said was “the big golf circuit" in his first year — a battered, blue Bedford door-mobile to be precise. Or as he says himself: “A £50 bricklayer’s van.”

Studiously cleaning the shaft of a persimmon wood for the camera and wearing slacks that clearly weren’t long enough to reach his ankles, the viewer is left to wonder how this giraffe of a man planned to insert himself in the back of this vehicle and get some sleep. A folded mattress rests against the back of a driver’s seat that appears to be made of the same red leather used to make his golf bag, practice bag and wood covers, while a pair of forlorn desert boots lie on the ground.

Of course, Jones’ golfing journey really began some three years earlier in 1966 when his parents allowed him to forgo a place at university (studying architecture) to indulge his passion for golf.

Playing off a modest seven handicap at the time - nothing unusual for assistant professionals in those days - he took a job as a lowly assistant pro in North Oxford as the general ‘dogsbody’ to the members, as he says on his website, “working every hour just to get better and escape”.

As luck would have it, he ended up working for an inspirational PGA professional who gave his dreams wings. “A really good guy called Nick Underwood, who was the guy who put me on my feet and made me believe in myself. A lot of people thought I was bonkers even turning pro, which I probably was by today’s standards.”

Little man, big man. David Jones with a very young Rory McIlroy.

The European Tour as we know it today did not exist at the time and little did this young Ulsterman now that he would end up becoming a member of its Board of Directors and the chair of the committee charged with finding a new CEO for what is now a global golf tour. He would also play the Underwood role to another enthusiastic assistant at Bangor during his first stint away from the tour - lifelong friend David Feherty.

Unlike the modern European Tour or even the Challenge Tour, where there is little time to learn, the late 60s and early 70s offered fledging pros the chance to earn their stripes, slowly but surely.

“Back then you had pre-qualifying and most of the tournaments were in Britain and a few in Ireland and you could work your way up the ranks from the very bottom, like I did and Eddie Polland and Darce and Christy Jnr and all my contemporaries,” he explains. “You went off to your pre-qualifying, you shot 80, you went back to your job on the Tuesday and you taught and cleaned shoes. Then you went to the next one, probably just down the road the next week, and slowly but surely you learned how to pre-qualify. And slowly but surely you learned how to make cuts.

“Of course, those days are gone now and you have to be a really whizz amateur [and playing at the very highest level] to get through Q-School. There was no Q-School back then, you just kept grafting away and if you were good enough you made it and if you weren’t you ended up teaching somewhere and that was about the height of it.”

Born in 1947 in Newcastle, Co Down, Jones had only been playing golf for two years when he went off to North Oxford as an innocent 19-year-old in 1966.

“I just loved it,” he says. “I was lucky along the way and met some great people. Nick Underwood gave me a lot of help and encouragement and off I went on the road in my £50 bricklayer’s van, sleeping in the back of that for a year. You just made your way like that.”

It wasn’t a lucrative enterprise and while he had had some success on the Safari circuit, common sense dictated that he took the professional’s job at Bangor when his second son Michael was about to be born in 1976.

“There was no real money in it unless you were a Christy O’Connor or a Peter Alliss,” he recalls. “If you were propping up the field at 50th or 60th, it was literally a tenner at a time.”

The stint at Bangor provided Jones and his family some stability and it also afforded him the opportunity to work on his game. He would go on to win consistently on the Irish and British club pro’s circuit, claiming the British Club Professionals Championship three times plus the Irish Match Play and 1981 Irish PGA at Woodbrook.

“I couldn’t wait to get back on the tour,” he says. “I was a better player and I had a bit of confidence. I had a bit of my own money behind me and I played well. I had minor successes, a lot of top 10s and top 5s, but I never really hit the big time. I enjoyed it and met some great people along the way.”

There were still successes ahead, such as the 555 Kenya Open in 1989. But by 1987 Jones was 40 and struggling to compete.

“I was going to stop playing in ’87 when I got the job as the Irish coach with the GUI. But that didn’t really work out for me and the GUI probably didn’t feel they were ready for a full time coach and it was difficult.

“You had limited access to the players, they had limited access to you. It wasn’t really a well-constructed programme so I went back on tour for another two or three years at the age of 40 and it was on and off. I went to the tour school and made my one and only visit in 1988 as an ethnic group of one - a [lone] 41-year-old.”

Antalya Golf Club's Pasha Course is a hugely successful David Jones design. Picture via DavidJonesGolf.com

What happened next changed the course of Jones’ career. He was asked to toughen up Killarney for the Irish Open, which was to be played at the Kerry venue in 1991 and 1992 and from there a new career took off.

“It was well received by the players - Faldo and the late Payne Stewart and Jose Maria Olazabal paid me some nice compliments and the phone started to ring and my second career started,” he says of what is now David Jones Golf Design and Consultancy.

“Feherty and I had always promised we would start a design company with him as the signature name and me doing the designs. So in 1990 we started a company called Handmade Designs and got a few jobs in Turkey and elsewhere but, of course, he went to the States and that broke up and I continued on my own.”

While his work in Ireland has been largely limited to redesigns of classic courses such as Mullingar or Balmoral, his work abroad has been on a large scale and received high praise in countries as far afield as Turkey, Finland, Kenya and Tanzania.

David Jones

“I have done 17 full scale developments and they have done well here and there, though the ones in turkey are the best known - Antalya Golf Club where Rory (McIlroy) and Tiger (Woods) played that exhibition event and were very complimentary. The courses in Africa are the most spectacular and dramatic.”

Few people get to design with Mount Kilimanjaro as a backdrop but Jones does not need to be reminded how fortunate he has been in his career.

Being a person of imposing physical stature has its advantages but Jones has combined that with a keen intelligence and innate sense of integrity to become one of the most respected figures within the European Tour.

“Whatever success I have had along the way or whatever impression I have made, it has stuck,” he says. “I am 67 now and still getting a lot of fun and satisfaction out of being a golf pro.”

He will be 50 years a pro in June 2016 and yet he still looks forward to each day with the enthusiasm of that 19-year-old with the Bedford van.

“I have had a good run, tried everything from playing and teaching to commentary for the BBC and course design and I’ve enjoyed everything. I’ve made great friendships that have lasted forever. That’s what golf is - a life study, a life time game.”

Jones believes there are new challenges ahead, not just for designers battling the demands placed on them by new technology, but also for the European Tour in a global age when the PGA Tour dominates the stage with its huge financial clout.

Getting the loyalty of the European players is key for Jones, but there is also a huge onus on the new CEO of the tour to get the balance right and strengthen Europe at key times of the year.

While appearance fees have always played a key role, greater emphasis now needs to be put on prize funds that can compete with the American model.

“The players are there, the talent is there and the money is there. It is just about making it all work in a worldwide context,” he says. “We have the final series now and we are looking at having a ‘series of series’ if you like - two or three events in the spring, three or four in the summer and then lead into the Final Series to make it easier for players to honour their European roots. Whether they are Swedish, English or Irish or whatever they support their national opens for real money - €10million purses - and build the European Tour into the Rest of the World tour if you like.

The caption says it all.

“The PGA Tour recognises that golf in the world is made more valuable by having these strands, the Far East, the Middle East, Europe, the States, maybe South America and Australia. It’s not going to be a completely one dimensional game.”

Rory McIlroy’s decision to host the Irish Open appears to be a sign of things to come.

“If you can replicate that in Germany with Kaymer and with Bjorn and Stenson or with the English players,” adds Jones. “If the world’s top European players take ownership of their national opens and push them up to a different level and use their influence to bring in a few top players and put it on the map, that’s probably the way forward.”

Whoever Jones and his fellow committee members decide to appoint as the successor to George O’Grady, he or she is sure to share a great affinity with the PGA.

“I am proud to be a member of the PGA,” says Jones. “When I was awarded Master Professional status in 2009, it was a great honour. It recognises the breadth of the career I have been fortunate enough to have.

“I value my PGA membership very highly, even though I am not in the club pro ranks any more. That is what started me off and in many ways my ability to be a teacher or commentator has come from my background as a PGA pro. It gives you a good grounding in how to be a pro. If you are a great young player and don’t ever need to go beyond playing, that’s fantastic. But if you are looking for a career in the game, playing can be part of it but being a PGA pro is a tremendous asset too.”